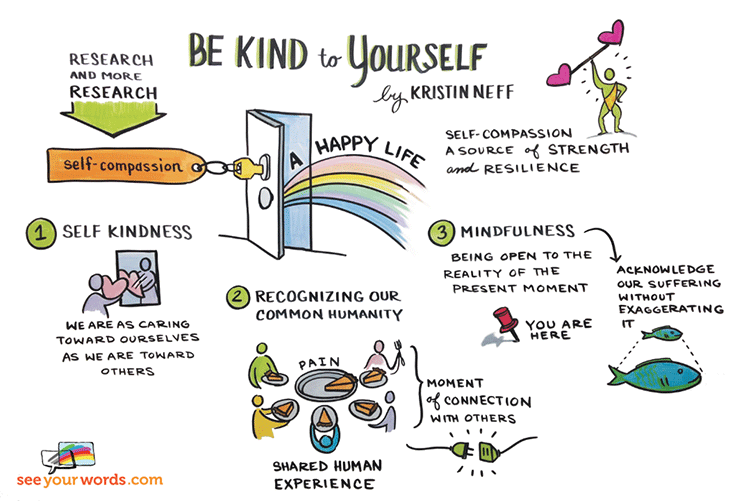

Self-compassion seems like a simple concept: direct compassion toward yourself like you do to others. But it’s incredibly common, especially with those who struggles with their mental health, to disregard the importance of being kind to yourself. Per Dr. Kristen Neff, an expert in self-compassion and how it affects people: Self-compassion involves acting the same way towards yourself when you are having a difficult time, fail, or notice something you don’t like about yourself. Instead of just ignoring your pain with a “stiff upper lip” mentality, you stop to tell yourself “this is really difficult right now,” how can I comfort and care for myself in this moment?

Self-compassion consists of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness.

1) Self Kindness (vs. Self Judgment) refers to:

- Treating yourself with care and understanding rather than harsh judgment

- Actively soothing and comforting, supporting to protect self

- Having the desire to alleviate suffering (any pain or emotional discomfort)

2) Common Humanity (vs. Isolation) means:

- Seeing your own experience as part of the larger human experience

- Understanding that it is normal to suffer and struggle

- Recognizing that life is imperfect (us too)!

Our unconscious assumption is that normal is perfect. This, in turn, leads us to feel isolated in our suffering when something goes wrong. When you realize and acknowledge how suffering is part of life and that we all suffer, you are no longer alone in your pain, and are more likely to share what is going on with someone and be comforted.

In addition, it may sometimes be beneficial to consider that whatever you are going through could be worse, and it could be better.

3) Mindfulness (vs. Over Identification) helps us:

- Accept, or “be” with powerful feelings as they are

- Avoid the extremes of suppressing, or running away with painful feelings

Some of us may like the idea of self-kindness but have a few misgivings about actually employing it towards ourselves. We assume that it may be indulgent, self-centered, or take away our drive and motivation to succeed. Neff explains how research shows that these misconceptions are false.

In reality, self-compassion decreases negative emotions/results, and increases positive emotions/results!

Specifically, self-compassion is positively linked to coping and resilience. For example, Neff shares that when employing self-kindness, veterans are less likely to suffer from PTSD than those who beat themselves up, and individuals are better able to cope with divorce and get through hard times.

Self-compassion is also positively associated with motivation. This is because when you are less afraid of failure/mistake, you are more likely to try again and persist in efforts after a failure. You are also more likely to take responsibility for mistakes and have the motivation to fix them. Therefore, address test (or interview) anxiety with self-compassion. You are more likely to be able to pick yourself again if you don’t do well on the test (or interview).

In addition, self-compassion is a valuable tool for caregivers (and mental health professionals). It helps them experience less burnout and caregiver fatigue, as well as greater satisfaction with caregiver role.

Suffering = Pain x Resistance (exponential rather than multiplicative)

Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional. We add on suffering when we resist the pain.

As Neff explains, if you resist your pain, compassion will fail you. In a moment of struggle, we give ourselves compassion, not to feel better but because we feel bad. Self-compassion provides the emotional safety needed to mindfully be open to our pain.

Fortunately, this isn’t just wishful thinking about another self-help approach. In fact, there’s now an impressive and growing body of research demonstrating that relating to ourselves in a kind, friendly manner is essential for emotional wellbeing. Not only does it help us avoid the inevitable consequences of harsh self-judgment—depression, anxiety, and stress—it also engenders a happier and more hopeful approach to life. More pointedly, research proves false many of the common myths about self-compassion that keep us trapped in the prison of relentless self-criticism. Here are five of them.

- Self-compassion is a form of self-pity

One of the biggest myths about self-compassion is that it means feeling sorry for yourself. In fact, as my own experience on the playground exemplifies, self-compassion is an antidote to self-pity and the tendency to whine about our bad luck. Research shows that self-compassionate people are less likely to get swallowed up by self-pitying thoughts about how bad things are. That’s one of the reasons self-compassionate people have better mental health.

- Self-compassion means weakness

Researchers are discovering that self-compassion is one of the most powerful sources of coping and resilience available to us. When we go through major life crises, self-compassion appears to make all the difference in our ability to survive and even thrive.

- Self-compassion will make me complacent

Perhaps the biggest block to self-compassion is the belief that it’ll undermine our motivation to push ourselves to do better. The idea is that if we don’t criticize ourselves for failing to live up to our standards, we’ll automatically succumb to slothful defeatism.

If we can acknowledge our failures and misdeeds with kindness—”I really messed up when I got so mad at her, but I was stressed, and I guess all people overreact sometimes”—rather than judgment—”I can’t believe I said that; I’m such a horrible, mean person”—it’s much safer to see ourselves clearly. When we can see beyond the distorting lens of harsh self-judgment, we get in touch with other parts of ourselves, the parts that care and want everyone, including ourselves, to be as healthy and happy as possible. This provides the encouragement and support needed to do our best and try again.

- Self-compassion is narcissistic

In American culture, high self-esteem requires standing out in a crowd—being special and above average. How do you feel when someone calls your work performance, or parenting skills, or intelligence level average?

Indeed, the emphasis placed on self-esteem in American society has led to a worrying trend: researchers Jean Twenge of San Diego State University and Keith Campbell of the University of Georgia, who’ve tracked the narcissism scores of college students since 1987, find that the narcissism of modern-day students is at the highest level ever recorded. They attribute the rise in narcissism to well-meaning but misguided parents and teachers, who tell kids how special and great they are in an attempt to raise their self-esteem.

But self-compassion is different from self-esteem. Although they’re both strongly linked to psychological wellbeing, self-esteem is a positive evaluation of self-worth, while self-compassion isn’t a judgment or an evaluation at all. Instead, self-compassion is way of relating to the ever-changing landscape of who we are with kindness and acceptance—especially when we fail or feel inadequate. In other words, self-esteem requires feeling better than others, whereas self-compassion requires acknowledging that we share the human condition of imperfection.

- Self-compassion is selfish

Unfortunately, the ideal of being modest, self-effacing, and caring for the welfare of others often comes with the corollary that we must treat ourselves badly. This is especially true for women, who, research indicates, tend to have slightly lower levels of self-compassion than men, even while they tend to be more caring, empathetic, and giving toward others. Perhaps this isn’t so surprising, given that women are socialized to be caregivers—selflessly to open their hearts to their husbands, children, friends, and elderly parents—but aren’t taught to care for themselves. While the feminist revolution helped expand the roles available to women, and we now see more female leaders in business and politics than ever before, the idea that women should be selfless caregivers hasn’t really gone away. It’s just that women are now supposed to be successful at their careers in addition to being ultimate nurturers at home.

Because we evolved as social beings, exposure to other people’s tales of suffering activates the pain centers of our own brains through a process of empathetic resonance. When we witness the suffering of others on a daily basis, we can experience personal distress to the point of burning out, and caregivers who are especially sensitive and empathetic may be most at risk. At the same time, when we give ourselves compassion, we create a protective buffer, allowing us to understand and feel for the suffering person without being drained by his or her suffering. The people we care for then pick up our compassion through their own process of empathic resonance. In other words, the compassion we cultivate for ourselves directly transmits itself to others.

When we care tenderly for ourselves in response to suffering, our heart opens. Compassion engages our capacity for love, wisdom, courage, and generosity. It’s a mental and emotional state that’s boundless and directionless, grounded in the great spiritual traditions of the world but available to every person simply by virtue of our being human. In a surprising twist, the nurturing power of self-compassion is now being illuminated by the matter-of-fact, tough-minded methods of empirical science, and a growing body of research literature is demonstrating conclusively that self-compassion is not only central to mental health, but can be enriched through learning and practice, just like so many other good habits.

Therapists have known for a long time that being kind to ourselves isn’t—as is too often believed—a selfish luxury, but the exercise of a gift that makes us happier. Now, finally, science is proving the point.