Tourette Syndrome is estimated to be present in about one out of every 160 children between ages 5-17 and is three times more likely to appear among males than females. It is also estimated that less than half of people living with Tourette Syndrome end up diagnosed with it.

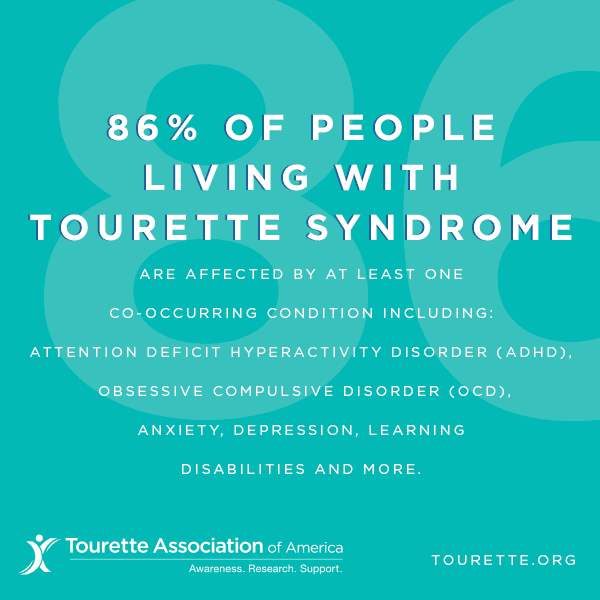

Tourette Syndrome is a neurological disorder resulting in involuntary verbal and motor tics. To reach a full diagnosis, a person must show a combination of one verbal tic and two different motor tics that last over one year. Other tic disorders may be diagnosed if that initial criterion is not met, but the stigma faced by tic sufferers, and the interventions available, are similar no matter the official diagnosis. Tourette and other tic disorders are also often found occurring alongside ADHD, OCD, learning disabilities, or anxiety.

What are the signs and symptoms of Tourette syndrome?

The motor (involving movement) or vocal (involving sound) tics of Tourette syndrome are classified as either simple or complex. They may range from very mild to severe, although most cases are mild.

Simple tics: sudden, brief, repetitive movements that involve a limited number of muscle groups. They are more common than complex tics.

Complex tics: distinct, coordinated patterns of movement involving several muscle groups.

Examples of motor tics seen in Tourette syndrome

- Simple motor tics include eye blinking and other eye movements, facial grimacing, shoulder shrugging, and head or shoulder jerking.

- Complex motor ticsmight include facial grimacing combined with a head twist and a shoulder shrug. Other complex motor tics may appear purposeful, including sniffing or touching objects, hopping, jumping, bending, or twisting.

Examples of vocal (phonic) tics in Tourette syndrome

- Simple vocal tics include repetitive throat clearing, sniffing, barking, or grunting sounds.

- Complex vocal ticsmay include repeating one’s own words or phrases, repeating others’ words or phrases (called echolalia), or more rarely, using vulgar, obscene, or swear words (called coprolalia).

Some of the most dramatic and disabling tics may include motor movements that result in self-harm such as punching oneself in the face or vocal tics such as echolalia or swearing. Some tics are preceded by an urge or sensation in the affected muscle group (called a premonitory urge). Some with TS will describe a need to complete a tic in a certain way or a certain number of times to relieve the urge or decrease the sensation.

Tic triggers

Tics are often worse with excitement or anxiety and better during calm, focused activities. Certain physical experiences can trigger or worsen tics; for example, tight collars may trigger neck tics. Hearing another person sniff or clear the throat may trigger similar sounds. Tics do not go away during light sleep but are often significantly diminished; they go away completely in deep sleep.

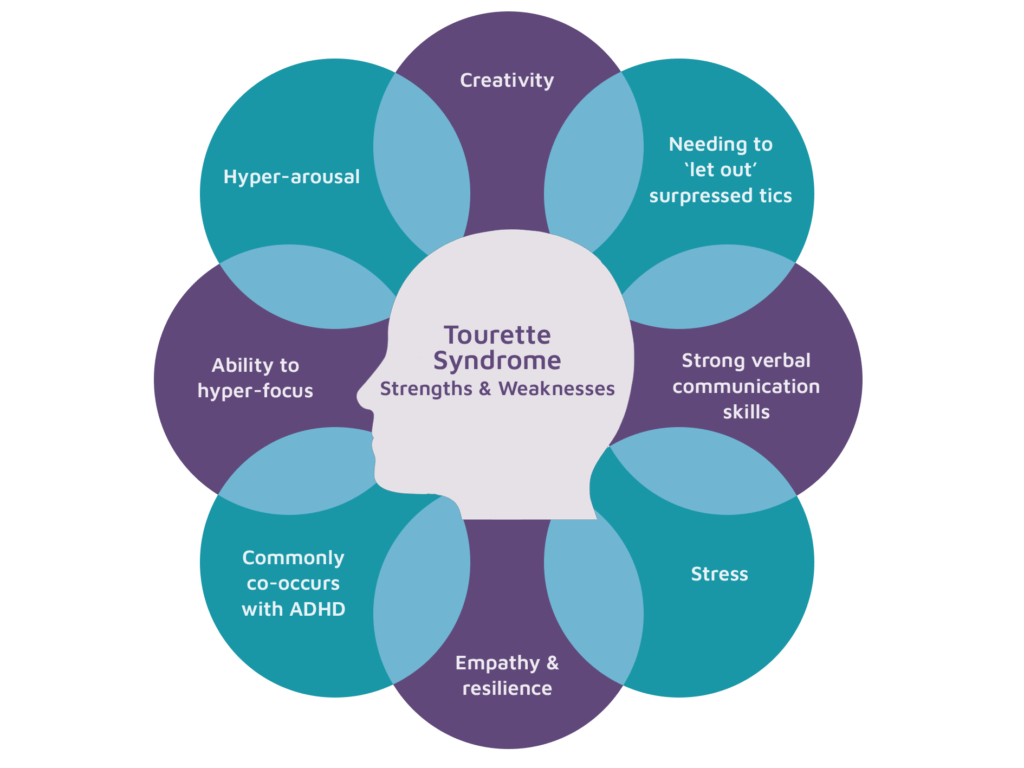

Although the symptoms of TS are unwanted and unintentional (called involuntary), some people can suppress or otherwise manage their tics to minimize their impact on functioning. However, people with TS often report a substantial buildup in tension when suppressing their tics to the point where they feel that the tic must be expressed (against their will). Tics in response to an environmental trigger can appear to be voluntary or purposeful but are not.

Disorders Associated with TS

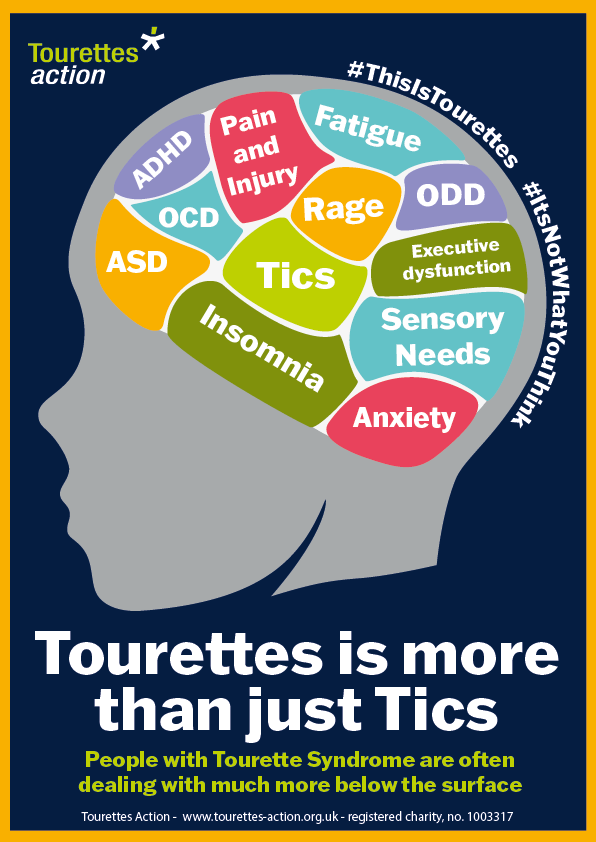

Many individuals with TS experience additional co-occurring neurobehavioral problems (how the brain affects emotion, behavior, and learning) that often cause more impairment than the tics themselves. Although most individuals with TS experience a significant decline in motor and vocal tics in late adolescence and early adulthood, the associated neurobehavioral conditions may continue into adulthood.

The most common co-occurring conditions include:

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), including problems with concentration, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder or Behaviors (OCD/OCB): repetitive, unwanted thoughts, ideas, or sensations (obsessions) that make the person feel the need to perform behaviors repeatedly or in a certain way (compulsions). Repetitive behaviors can include handwashing, checking things, and cleaning, and can significantly interfere with daily life.

- Anxiety (fear, unease, or apprehension about a situation or event that may have an uncertain ending).

- Learning disabilities such asproblems with reading, writing, and arithmetic that are not related to intelligence.

- Behavioral or conduct issues, including socially inappropriate behaviors, aggression, or anger.

- Problems falling or staying asleep.

- Social skills deficits and social functioning difficulties, such as trouble with social skills and with maintaining social relationships.

- Sensory processing issues, such asdifficulty organizing and responding to sensory information related to touch, taste, smells, sounds, or movement.

Educational Settings

Although students with TS often function well in the regular classroom, ADHD, learning disabilities, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and frequent tics can greatly interfere with academic performance or social adjustment. After a comprehensive assessment, students should be placed in an educational setting that meets their individual needs. Students may require tutoring, smaller or special classes, private study areas, exams outside the regular classroom, other individual performance accommodations, and in some cases special schools.

Tics can start and stop spontaneously, though exhaustion, excitement, stress, and anxiety (and even talking about them or pointing them out) can make tics worse. Tics vary greatly and can range from mild and barely noticeable to severe and majorly disruptive. Verbal tics can include throat clearing, coughing, whistling, repeating sounds or words or the very rare coprolalia (yelling offensive words).

Physical tics can involve head rolls, eye blinking, shrugging, hand movements, eye movements, etc. Tics can become painful, exhausting, and, at times, all-consuming. They can even qualify a person for disability in some cases.

Stigma surrounds those who deal with Tourette’s and other tic disorders. Most well-known is the idea that Tourette’s only causes people to yell out obscenities, and it is often used as an excuse or as the butt of a joke. In truth, coprolalia is extremely rare among people with Tourette Syndrome, and that stereotype can be harmful.

In addition, some may believe that people engage in tics for attention, or because they can temporarily repress the urge to tic in some situations that they must be faking it. Uncontrollable tics can make children more at risk for bullying. They can also affect education, whether the tics disrupt the classroom and/or concentration or medications cause attention issues. Many children and adolescents with tics are eligible for accommodations in school as a result.

While treatments exist for this condition, there is no known cure. Certain therapies, such as Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT), can help provide people with a feeling of control over their tics. Others choose (or require) medications. Speech therapy can help with minimizing vocal tics. For many, tics are a temporary issue they grow out of as adults or older adolescents, but then for others, they are a lifelong struggle.