Have you ever tried to unlock a door that wouldn’t open? At first, you think you might be doing something wrong. Maybe there’s a trick to it. You pull the key back a little—doesn’t work. You wiggle the key—doesn’t work. You keep trying, but the door stays locked. After a while, you realize the problem isn’t you, it’s the key.

This is what it’s like for minorities trying to access mental health care.

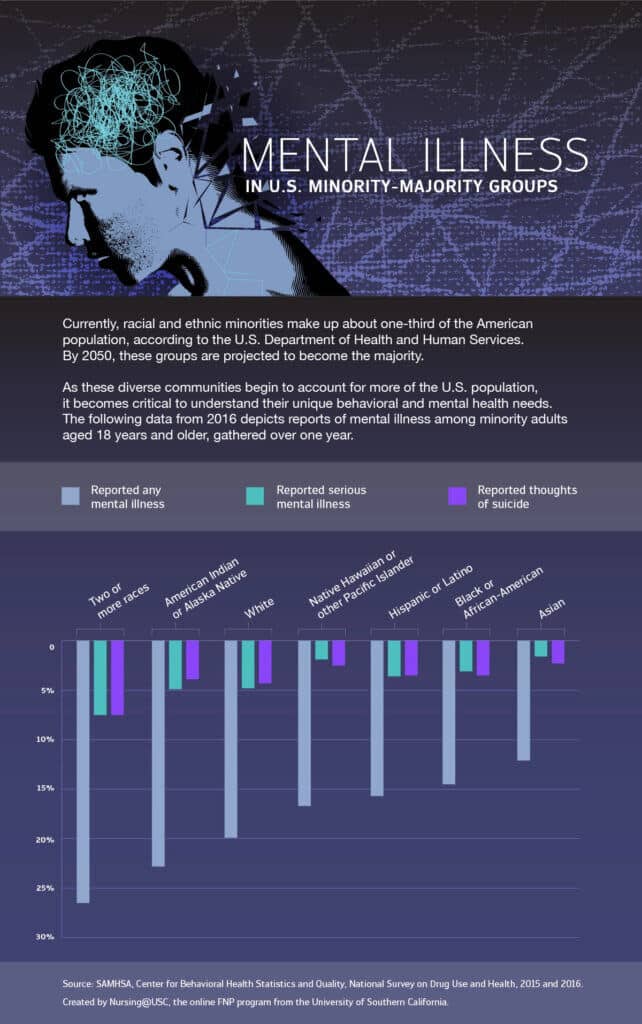

As hard as it is for anyone to get proper mental health care in the United States, it’s even harder for racial, ethnic, religious and gender minorities. Not only are there the problems most of us experience—issues with insurance, long wait times, difficulty finding specialists, sky-rocketing deductibles, and co-pays—but there are added burdens of access and quality-of-care.

Social Determinants of Mental Health

A deep dive into the forces that drive disparities in minority care often points to barriers to medical access. Access can be limited by lack of insurance coverage — and more than half of uninsured U.S. residents are people of color. People with limited resources also experience logistical barriers, such as taking time off of work, securing childcare or finding transportation to and from appointments. Linguistic and cultural differences — particularly for immigrant populations — can result in breakdowns in communication that lead to poorer health outcomes.

Lack of qualified, available professionals to evaluate, diagnose and treat such conditions is another factor fueling uneven coverage. Even in areas with high densities of mental health professionals, minority groups report high rates of poor mental health. According to data on mental health care professional shortages from the Kaiser Family Foundation, most states have met less than 50% of mental health care needs among their populations, citing dire provider shortages and vast disparities across racial and ethnic groups.

Why is this happening?

In high-risk areas, those who choose to seek treatment often receive inferior care because there tends to be little diversity among mental health providers and decreased understanding about the different mental health needs across minority groups. Even when language translation services are provided, lack of diversity breeds cultural insensitivities that lead to negative health outcomes, such as higher treatment dropout rates. Studies have shown that minorities are less satisfied with the quality of care they receive since they feel that providers simply do not understand their needs.

Provider discrimination also affects the quality of care that minority populations receive. Though all discrimination is harmful, an examination of the effects of racism — the most commonly studied and cited form of discrimination — reveals implications for the mental health of individuals in minority groups.

Although provider discrimination and cultural microaggressions can be subtle, the implications are great: Studies have documented how physicians were less likely to identify the severity of depression among minority patients versus white patients. Often, a clinician with the false assumption that mental health needs are less prevalent among minorities may be less likely to recommend treatment in comparison to a white patient with similar symptoms. With these studies in mind, racism is not only a civil rights issue but also a public health concern.

Other factors can be classified as social determinants of health (SDOH), which have a major influence on health outcomes. The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion defines social determinants of health as “conditions in one’s environment — where people are born, live, work, learn, play, and worship — that have a huge impact on how healthy certain individuals and communities are or are not.” In diverse populations, these determinants underscore the current rates of suicides and mental health disorders reported in the United States.

Most notably, lack of income triggers depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and minorities statistically are more likely to straddle the poverty line throughout their lives. They are also less likely to get help. The following graphic displays the self-reported barriers to pursuing mental health care as indicated by adults in the United States who had an unmet need for services between 2008 and 2012.

How Providers Can Address Minority Mental Health

Closing the gap in minority mental health cannot be fixed overnight. It will require a widespread and collective effort to account for all underserved populations and tailor interventions to satisfy their unique challenges. Primary care providers can help break down barriers by educating themselves — as well as their colleagues and communities — on the ethnic and cultural gaps among patient populations.

Providers should consider their own values and how perceptions may influence interactions with patients from other cultures. Listening to minority patients’ needs and helping them to feel safe and understood can empower them to get the mental health treatment they deserve and to live productive and fulfilling lives.

Primary care providers, including family nurse practitioners, are integral to ensuring all patients receive comprehensive care, and they serve as a key resource for those most vulnerable to the negative health effects resulting from discrimination.

“We are teaching our students about the central importance of social determinants of health, with racism being a key determinant, in the health of individuals and families,” said Ellen Olshansky, professor and chair of University of Southern California’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work Department of Nursing.

Communities at highest risk for discrimination are the same communities that are perpetually marginalized by the negative impact of SDOH. In the Atlantic, writer Jason Silverstein points out that the cyclical effect of discrimination on health is what is referred to as “embodied inequality,” which creates poor health outcomes that are often passed down through generations. This results in a vicious cycle where the sickest and poorest among us are more likely to remain sick and poor.

Improving Access to Mental Health Resources

What specific steps can be taken to reduce the disparities in mental health care for minorities? Health care professionals and policymakers can play a key role in curbing discrimination by supporting legislation and policies that address these issues, such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. The U.S. Office of Minority Health serves as a “source for minority health literature, research and referrals for consumers, community organizations and health professionals.” By using available resources and appropriate support networks, victims of discrimination can find the support they need to exercise their rights and end the various forms of discrimination they may be vulnerable to.

Providing access to necessary resources and additional support for these patients is critical. Here are some starting points:

- Education and awareness: Despite progress in recent years, there is still a stigma associated with mental illness. Embarrassment can be lessened by helping people in at-risk communities understand that mental health is an essential part of well-being — just like a healthy diet, sleep and exercise. Initiatives such as Mental Health First Aid endorsed by Michelle Obama, are helping people to better understand and respond to signs of mental illness.

- Policy changes: Universal mental health care coverage would dramatically improve access for minorities. Quality improvement efforts include screening, cultural sensitivity training and language-appropriate treatment and educational materials. At the federal level, policies would assist in training a diverse workforce to adequately meet America’s mental health needs.

- Advocacy and outreach: Public health advocates have proven effective in reducing barriers to care for at-risk communities. For instance, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration created the Office of Behavioral Health Equity (OBHE), which aims to eliminate disparities in mental and/or substance abuse disorders across all populations. OBHE’s outreach strategies include helping underserved racial and ethnic groups within communities understand the importance of maintaining good emotional health.

- Integrating behavioral health with primary care: In minority communities where specialists are not plentiful, identifying a mental health practitioner can be a challenge. However, integrating mental health care with primary care could reduce disparities in access to care and could increase the odds of identifying a patient’s mental illness.

Additionally, it is essential that health care professionals work to better recognize the effects of discrimination by taking SDOH into consideration as part of their approach to care, understanding which populations may be at greater risk for discrimination screening for negative mental health outcomes that may be a direct result, and ensuring that discrimination is not occurring within their own practice settings.

Next Steps for Healthcare Leaders

When it comes to the mental health and well-being of our patients, staff, and communities, we as leaders must resist engaging in “magical thinking” and “time heals all” idealism. It’s our responsibility to recognize the societal and system barriers faced by minorities and work to cultivate equity for the people whose lives we touch through our healthcare organizations. We must be brave and resist upholding the status quo purely to avoid “upsetting the apple cart” and making some people uncomfortable.